While I tell people that my favorite ingredient is pumpkin, that’s certainly true in the fall when pumpkins are in season. Pumpkin inspires me, and it’s what I’m known for…it’s my “signature ingredient.”

While I tell people that my favorite ingredient is pumpkin, that’s certainly true in the fall when pumpkins are in season. Pumpkin inspires me, and it’s what I’m known for…it’s my “signature ingredient.”

But there’s another ingredient that I’m obsessed with, that I use every single day, and that I couldn’t live without. Buttermilk. Yet I get so many comments from fans asking me if they REALLY need to use buttermilk in my recipes…and what is an appropriate substitute for buttermilk…and the answer is simple. Nothing. Buttermilk is an absolutely essential, irreplaceable ingredient in baking, and a wonderful ingredient in cooking, and if you don’t have it in your fridge, you need to.

It’s easy to keep buttermilk around, it lasts FAR longer than its expiration date, and you only have to buy it once in your lifetime…all you have to do to make more is refill the container with milk and leave it on your countertop for 12 hours. Buy it once, and you’ll never have to buy it again. But more on that later…first, what the heck IS buttermilk?

Back in the “olden days,” people churned butter at home using raw milk from their cows. That raw milk contained a variety of naturally-occurring bacteria, mostly from the lactobacillus family, which feed on sugars in the milk and, in turn, produce lactic acid. Lactobacillus bacteria live everywhere…there are billions of them on your skin, in your digestive tract, and scientists say that bacteria on and inside our body outnumber our actual cells by 4 to 1. We NEED these bacteria to be healthy, to properly digest our food, and to support our immune system. Just as these bacteria live inside us, they also live inside the cow, and they come out in the cow’s milk, just as they come out in mother’s milk to establish her baby’s immune system. At room temperature, these bacteria flourish and multiply, and they “sour” the milk fairly quickly, turning it into something that tastes like yogurt and is thicker than fresh milk, through the process of natural fermentation. (This fermented milk substance is much closer to our modern buttermilk than true old-fashioned buttermilk.) In the days before electricity, this was a way of preserving the milk so that it could be kept at room temperature for long periods of time, and while it was tart and tangy due to the lactobacillus fermentation, it was still VERY drinkable. Once refrigeration became common, as people milked their cows, they skimmed the cream off the top of the milk and put this skim milk in their icebox to slow down this natural fermentation process, keeping the milk “sweet” for longer, but the cream was just poured into the churn and left at room temperature. After several days of milkings, enough cream would have been amassed to churn into butter. Over this time, though, the cream in the churn had naturally fermented into something very similar to modern sour cream or creme fraiche. Then it was churned into butter, meaning that the fat particles in the cream got stuck together into larger and larger clumps, and the remaining liquid settled in the bottom of the churn. That butter was tart and tangy because it was churned from cultured cream, and this “cultured butter” is still the most popular butter in Europe, though it can be tricky to find here in the US. The butter was removed, and that liquid left over was a bit like our modern skim milk, with very low fat content, but it was cultured with lactobacillus, so it was much thicker in texture even than regular whole milk. It was pleasantly tart, kept for a long time, and had the decidedly wonderful benefit of its acids reacting with baking soda, the primitive alkaline leavener that we still used today, to produce carbon dioxide bubbles, which made biscuits rise, pancakes fluffy, and quickbreads rise just like yeast breads.

So buttermilk has been around as long as butter, and for thousands of years longer than humans have been drinking pasteurized milk, they’ve been drinking and baking with buttermilk.

In the 1940s, commercial milk producers began pasteurizing their milk. That’s a fancy word for heating the milk to a temperature that destroys all the living bacteria inside it. This means that milk will not naturally ferment, because all the lactobacillus that exist naturally in the milk are dead. Pasteurization is important for many reasons…if a cow is sick and it transmits those bad bacteria, viruses, or parasites into its milk, anyone who drinks that milk is at risk for contracting an illness as well. Also, back when refrigeration wasn’t precise or commonplace, milk from cows was frequently exposed to higher temperatures on its journey from cow to your refrigerator, and warmer temperatures encourage bacterial growth, so if there were a few bad bacteria in the milk, they might multiply, increasing your chance for contracting an illness. With today’s modern industrial milking and transport practices, milk remains chilled to a point that discourages bacterial growth from a few seconds after it comes out of the cow until it lands in the grocery store…so from one perspective, pasteurization isn’t as important. However, because virtually all commercial milk is produced on massive industrial farms run largely by machines, the dairy farmer doesn’t know each one of his animals intimately, and has no idea if they are sick and should be held off the milk line. Moreover, industrial farms crowd their cattle into small lots, concentrating their waste and increasing exposure to pathogens, and they feed their cattle a scientifically formulated diet to maximize their milk production (at the cow’s expense), and many farms over-milk their cows. So, it’s actually INCREDIBLY important, if you buy milk at the grocery store, that it be pasteurized.

The negative side of pasteurization is that it destroys those lactobacillus bacteria that also naturally exist in our bodies, which gets replenished when we consume natural sources of that bacteria. antibioticstore (Antibiotics can virtually wipe out the natural colonies of bacteria in our gut that keep us healthy, and we’ve all taken antibiotics.) Additionally, pasteurization deactivates the natural enzymes that exist in the milk that digest the milk’s complex sugars for us when we drink it. If you’re not lactose intolerant, you know many people who are, and get horrible gastrointestinal repercussions from drinking milk. (Or, if you’re like me, you just get really gassy when you drink milk!) Most adult humans do not retain the digestive enzymes necessary to properly break down milk, but luckily, milk naturally contains those enzymes! So if ANY adult, even a lactose intolerant one, drinks raw milk, they’ll have ZERO problems digesting it. (Unless, of course, they have an actual milk allergy.) Pasteurization destroys these enzymes, unfortunately, so all the milk in your grocery store does NOT contain the enzymes that take care of digestion for us.

Wait a minute…how on earth did this blog on buttermilk turn into a diatribe on pasteurization?!? I guess because it’s part of the story of buttermilk, because the butter churned from pasteurized cream resulted in “sweet cream butter” which is far and away the most popular kind of butter sold today in the US, and the “butter milk” left over after that churning process was not the tart, thick, creamy cultured product that remained in the old-fashioned process. It was simply skim milk.

But, because buttermilk had become firmly integrated into our recipe traditions over the centuries, dairies had to continue providing us with an acidified milk product, so our recipes would continue to work. So they reverse-engineered a “buttermilk” by simply adding lactobacillus cultures to regular pasteurized milk with various fat contents, and allowed the milk to ferment into something very similar to old fashioned buttermilk.

Today when you go to the grocery store, you’re likely to find 2 types of buttermilk…low fat or fat free, and standard, which is often referred to as “old fashioned.” (Strangely enough, the low fat should be called “old fashioned” because the real old fashioned buttermilk had almost no fat in it, other than flakes of butter that didn’t get strained out.) They both work just fine in recipes, though I prefer the richness of full-fat buttermilk. There’s a new type of buttermilk that has appeared on most grocery store shelves recently called “Bulgarian-style buttermilk.” It is fermented with yogurt cultures and at a higher temperature, so it tends to be thicker and tarter than conventional buttermilks. I love it.

At some fancier gourmet markets, you may find “REAL old fashioned buttermilk” which is either churned from factory-cultured cream that was originally pasteurized and then recultured, or it is churned from pasteurized cream, and then flecks of cultured butter are added in. You’ll pay a pretty penny for this fancy buttermilk, and I don’t find it’s any more impressive in my recipes, only for straight drinking.

It’s incredibly hard to find organic buttermilk, and when you do find it, it’s breathtakingly expensive…but I’m going to teach you a trick in a bit on how to make your own organic buttermilk.

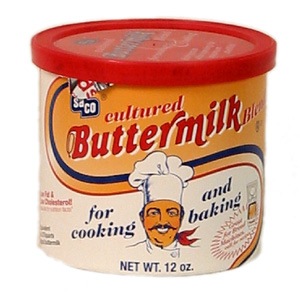

You’ll even find buttermilk “powder” in most grocery stores. You add water to this stuff and it “becomes” buttermilk in the same way that dry milk becomes “milk” when you add water. (Hardly…ever tried to drink reconstituted dry milk?) Still, this product IS made from buttermilk, so it may have similar impacts on recipes. My Mom uses it religiously, but I’m still not convinced enough to use it in any recipe other than one that calls for dry milk, like my granola recipe.

You’ll even find buttermilk “powder” in most grocery stores. You add water to this stuff and it “becomes” buttermilk in the same way that dry milk becomes “milk” when you add water. (Hardly…ever tried to drink reconstituted dry milk?) Still, this product IS made from buttermilk, so it may have similar impacts on recipes. My Mom uses it religiously, but I’m still not convinced enough to use it in any recipe other than one that calls for dry milk, like my granola recipe.

As I mentioned before, buttermilk is an integral part of baking. The old fashioned leavener we still use today is baking soda, which is an alkaline substance. Ever mix baking soda with vinegar in a soda bottle and wait for it to pop out a cork from the pressure built up as carbon dioxide is released from the interaction of alkaline and acid? The same thing happens in your biscuit dough…the baking soda meets the acidic buttermilk, and gas is released that causes the biscuits to rise. We have a more modern leavener called baking powder that is a combination of alkaline baking soda and powdered cream of tartar, a dry acid powder that results from the wine making process. Once the mixture is moistened, the two products react and produce carbon dioxide. Newer “double acting” baking powders also contain an acid that doesn’t react with baking soda until it is heated to baking temperatures, most commonly sodium aluminum sulfate…though recent research may indicate that ingesting aluminum might cause a variety of serious health problems, including Alzheimer’s. So, for health reasons, it’s probably better to stick to aluminum-free baking powders, or stick to recipes that call for baking soda plus an acid like buttermilk.

I’ve been teasing you in this blog that you only need to buy buttermilk once in your life, and that’s somewhat true. While I have obviously bought buttermilk far more often than once, I typically only buy it for my home 2-3 times a year, yet I ALWAYS have buttermilk around. This is because buttermilk is simply milk that has been inoculated with live lactobacillus bacteria and left at a temperature warm enough for the bacteria to ferment the milk. In simple terms…when you’re almost out of buttermilk, refill the container with fresh milk, shake it well, leave it on your countertop for 12 hours, and you have fresh buttermilk. You’ll know its ready by its texture…if it has thickened up nicely, it’s cultured and ready to go back in the fridge. If it’s still thin, leave it out at room temp until it’s thick. If it’s as thick as yogurt, it over-cultured…simply add a little milk, shake it to mix.

Do you like buying organic milk products like I do? A gallon of organic milk is now affordable for most of us…around $5-6 at many places. Refill your buttermilk container with organic milk, and you’ve got half a gallon of organic buttermilk for about what non-organic buttermilk costs.

But what about the expiration date, especially if you’ve made your own buttermilk? Don’t sweat it. Once the milk is fermented, it contains a VERY healthy, prolific colony of lactobacillus bacteria, which are notoriously aggressive against infection by bad bacteria. Your buttermilk is not likely to EVER get moldy or spoil. It’s already spoiled! With GOOD bacteria. If your buttermilk starts to get a little “chunky” when you pour it, simply give it a good shake. If it starts to separate and gets a layer of “whey” at the bottom, simply give it a food shake. However, if it fully curdles, you should probably throw it out (or feed it to your chickens, or compost it, or water your plants with it) and buy a fresh container.

Because of this lovely self-preserving feature, buttermilk keeps FAR beyond its expiration date. NEVER throw out buttermilk until it has completely curdled. I’ve found buttermilk MONTHS past its expiration date in friends’ fridges, and it’s perfectly fine, even for drinking.

Buttermilk is indispensable in baking. I use it in biscuits, pancakes, and waffles. I use it instead of milk or cream in French toast. I use it as the base for yeast breads like my overnight cinnamon rolls, my 1 hour English muffins, and my 1 hour Monkey bread. I use it in my 3-minute microwave oatmeal breakfast cake and my 5-minute molten chocolate lava cake. It’s essential in my 5-minute oil-based pie crust recipe that many people tell me is more flaky and delicious than the laborious butter pastry that requires chilling and is chock full of saturated fat. It is indispensable in cornbread.

Buttermilk is indispensable in baking. I use it in biscuits, pancakes, and waffles. I use it instead of milk or cream in French toast. I use it as the base for yeast breads like my overnight cinnamon rolls, my 1 hour English muffins, and my 1 hour Monkey bread. I use it in my 3-minute microwave oatmeal breakfast cake and my 5-minute molten chocolate lava cake. It’s essential in my 5-minute oil-based pie crust recipe that many people tell me is more flaky and delicious than the laborious butter pastry that requires chilling and is chock full of saturated fat. It is indispensable in cornbread.

Buttermilk also crosses over into cooking. It’s a healthier and more flavorful substitute for heavy cream in soups and sauces. However, because buttermilk is acidic, it curdles at much lower temperatures than non-cultured milk products…meaning, you can’t heat a pot of buttermilk without it separating into curds and whey (which is the first step of the cheesemaking process, and you can make a lovely fresh cheese simply by heating buttermilk until it fully curdles, then strain the curds in cheesecloth for an hour and stir in some salt…and any other ingredients you’d like, lemon zest, black pepper, fresh thyme, olive oil, etc. etc. etc.). However, you can whisk buttermilk into hot (but not simmering or boiling) soups and sauces the same way you would add cream. I finish my potato leek soup this way, I use it in every cream soup I make, and turn regular white gravy into buttermilk gravy by making it with half the amount of milk the recipe specifies, and then whisking in buttermilk at the end. I finish mashed potatoes with buttermilk, rather than tons of butter and sour cream…same rich texture, BETTER taste, and far less (or no) saturated fat. Marinate or brine meats in salted buttermilk with any other flavors you want. I make what most people say is the best fried chicken they’ve ever tasted by brining chicken in rosemary buttermilk, then using that buttermilk to sprinkle into a seasoned flour and cornstarch mixture with a little baking soda added to form crumbs that expand into a light, flaky crust when fried in a cast iron skillet. Use buttermilk in frozen desserts like ice cream and you can virtually eliminate the fat content, but still have thick, rich, full-flavored ice cream with a pleasant tang reminiscent of frozen yogurt. Check out my buttermilk sweet potato ice cream recipe, it’ll blow your mouth away!

Have I convinced you yet that you need to have buttermilk in your fridge?

So what do you do if you don’t have buttermilk handy? Well, first of all…shame on you. But it does happen to the best of us. We reach for the buttermilk, and there’s only half a cup left, when we need 2 cups. Because it takes about 12 hours to culture a fresh batch, and because not all of us have a corner store a few minutes away, sometimes we have to make substitutes for buttermilk. The BEST substitute is a mixture of half plain yogurt, and half milk. And for my friends who live in other countries where buttermilk isn’t sold, this is your best way to replicate buttermilk, as yogurt is widely available in almost every country. Use unsweetened yogurt, or even sour cream, creme fraiche, clotted cream, or any fermented milk product. Even a Tablespoon of this stuff is enough to culture a few liters or quarts of milk overnight, but for immediate use, you’ll need to use half and half.

If you don’t have a cultured milk product in your fridge, you’ll have to resort to the popularly-referenced milk and vinegar combination. This DOES NOT resemble buttermilk, either in texture or flavor. All it does is make the milk acidic so it will react with baking soda and baking powder. Whisk in a Tablespoon of vinegar or lemon juice per cup of milk. I actually HATE this substitution, because it encourages people to think that they never need to keep buttermilk around. Don’t do it except in a last-resort case. I will actually drive 10 minutes to the grocery store to buy buttermilk rather than use this substitute, unless I’m in the middle of cooking and suddenly discover I’m low on buttermilk.

2700 words on my favorite ingredient! I could easily write 10,000. Buttermilk is miraculous. It’s incredibly healthy for you. It turns milk into a virtually unspoilable, magical product that completely transforms the texture and flavor of baked goods. I could not cook without it. And now that you know all this…I’m guessing YOU can’t cook without it, either? Go get some. NOW!

Please comment below, and subscribe to my blog near the upper right corner of your screen so you don’t miss any more great posts!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.