My wonderful neighbor Ron surprised me a few days ago with some cuts from a few wild boar he shot on a recent hunting trip. I took that as my excuse to get set up for home-curing…something I’ve been researching for a VERY long time.

Curing meat through the application of salt, occasionally smoke, and subsequent hanging to dry, is the oldest form of cooking. It’s been practiced by our ancestors for thousands of years. And cured meats are among the most sought-after and expensive artisan food products on the planet. Ever heard of Prosciutto di Parma or Prosciutto di San Daniele? How about Jamon Iberico or Speck? These are all dry cured hams from artisans in Europe, and they can run upwards of $1,000 PER HAM…or around $75 per pound. And the techniques used to cure these meats have been passed down through families for generations.

There was a time in our own country’s history where virtually everyone on the farm cured their own hams and bacon, so they could be hung in the cellar for months at a time, without requiring refrigeration. (When was the last time you saw a ham for sale that was hanging from the ceiling of the store, unrefrigerated, rather than in a cooler?) Properly cured hams can last 2 years without being refrigerated.

The process of curing concentrates the flavor of the meat into an explosive, pungent burst of taste in every thinly-sliced morsel. Virtually any meat can be cured. (There’s even such a thing as duck and ostrich prosciutto!) Wild meats are well-suited to curing, and in places where cured meats are eaten regularly, like Italy, wild boar meat is especially sought-after. So it made perfect sense when Ron gifted me 2 shoulders, 2 legs, and 2 loins that I cured them all. I selected traditional Italian recipes for the curing…and by “recipe” I really mean “method.” Salumi (the Italian word for meat curing) is the art of taking what nature has given us, and doing as little as humanly possible to make it the best it can possibly be. The recipes for the classic hams of Europe call for nothing more than meat and salt…and perhaps a bit of black pepper or wine. That’s all.

The starting point for curing meat is the salting procedure. Most recipes call for a salt addition equal to 8.5% of the weight of the meat. Which means you have to weigh your meat.

Here you see the shoulder, which will be cured into “spalla,” already rubbed with salt and black pepper. You can see the weight and salt requirement written on the parchment near the cut. It’s very critical when curing meats to minimize the amount of bacteria that come in contact with the meat. So always wash and sterilize your hands (or wear sterile rubber gloves), and work on surfaces that are immaculately clean. The salt helps prevent bad bacteria from growing on the meat, but the less bacteria the salt has to deal with, the better.

Here you see the shoulder, which will be cured into “spalla,” already rubbed with salt and black pepper. You can see the weight and salt requirement written on the parchment near the cut. It’s very critical when curing meats to minimize the amount of bacteria that come in contact with the meat. So always wash and sterilize your hands (or wear sterile rubber gloves), and work on surfaces that are immaculately clean. The salt helps prevent bad bacteria from growing on the meat, but the less bacteria the salt has to deal with, the better.

Above, you see the back legs (or hams) of the boar, which will be turned into prosciutto. Making the correct cuts for each type of salumi is WELL beyond the scope of this blog. (Book recommendations will follow.) For beginners, it’s best to leave the bone in the cuts while curing, because the more you slice into meat, the more crevices you leave for bacteria to take hold! Once the meat is prepared, you add 8.5% of the weight of the meat in salt. (I used Morton’s kosher salt.) Rub the salt all over the meat, and make sure to get into all the nooks and crannies of the meat, where the bacteria may be hiding, as you see in the photo to the left.

Above, you see the back legs (or hams) of the boar, which will be turned into prosciutto. Making the correct cuts for each type of salumi is WELL beyond the scope of this blog. (Book recommendations will follow.) For beginners, it’s best to leave the bone in the cuts while curing, because the more you slice into meat, the more crevices you leave for bacteria to take hold! Once the meat is prepared, you add 8.5% of the weight of the meat in salt. (I used Morton’s kosher salt.) Rub the salt all over the meat, and make sure to get into all the nooks and crannies of the meat, where the bacteria may be hiding, as you see in the photo to the left.

For some meat cuts, like the shoulder for making spalla, or the loin for making lonza, you can add some toasted, cracked black pepper to the salt:

Once the meat is salted, it’s time for pressing. For smaller cuts, like the loin, you can put them in a plastic ziploc bag with a bit of additional salt:

For the larger cuts, use a large pan, or if you don’t have one big enough, a black plastic garbage bag. For full sized hams, you want to lay them on a bed of salt, and pack additional salt around it, so that all surfaces are in contact with the salt:

Then you place it in the fridge and weigh it down. The amount of weight depends on the original weight of the meat. For prosciutto, you want to use a weight equal to the meat’s weight. So if it’s a 10 pound ham, you need to place 10 pounds of weight on top of it. It’s best to place a small baking pan on top of the meat, and then your weight. I used cast iron skillets and cast iron lids. You can use bricks, big cans of tomatoes…whatever you have. For smaller cuts like loin or shoulder, 8 pounds of weight is a good all-purpose weight.

Refrigerate the meat for 1 day per 2 pounds of weight. Every day or so, flip the meat in the salt and rub it with salt again. You’ll notice juices leaching out of the meat. If there’s enough juice to gather in the pan, pour off the juice. If there’s just a bit of juice, mix it with the salt and rub it back onto the meat when you flip it.

When the required salting time is finished, remove the meat from the salt and rinse it with cold water…then pat it dry with paper towels. Now it’s time for a wine bath! This optional step just involves bathing the meat in a dry white wine:

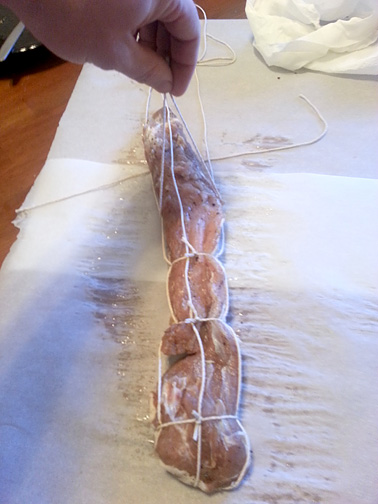

For pepper-rubbed cuts like lonza and spalla, you can now sprinkle finely-ground black pepper onto the meat, and it’s time to lay it on top of the twice that it will be hung with:

There are number of traditional ways of tying meat for hanging, but you can also improvise. Use all-natural string, like cotton twine. Don’t tie it too tight, just firm enough so that it can hang securely:

There are number of traditional ways of tying meat for hanging, but you can also improvise. Use all-natural string, like cotton twine. Don’t tie it too tight, just firm enough so that it can hang securely:

Once the meat is tied, it’s time to hang. Up to this point, no “special equipment” has been necessary to cure meat. But now, you need a temperature and humidity controlled environment that the meat can dry in. If you have a cellar or unfinished basement pretty much ANYWHERE in the country, the conditions there are probably ideal for meat curing. You want a temperature between 55 and 70 degrees, and a humidity level between 60 and 70 percent. If you don’t have a cellar or unfinished basement, you have to build yourself a curing “room.” I did it in an old refrigerator (which cost me $50 on Craigslist) plus about $150 worth of equipment to precisely control temperature and humidity. (Check out the blog post on how to convert a fridge into a curing chamber.) Some people cure in a mini-fridge turned to its warmest setting with a bowl of water added to contribute humidity, and have excellent results. So if you want to try home-curing on the cheap, that’s a great place to start. But unless you can accurately know and control your humidity and temp, don’t expect exceptional results.

The meat needs to hang until it has lost 30% of its post-salting weight. (So make sure to weigh your meat after the salting and pressing!) For small cuts like young wild boar, this can happen in a few months. For a large 25 pound ham, it can take a year. These 14 ounce lonzas at left will probably be cured in a month or two. The 4 pound hams will probably be cured in 4-6 months. The longer you cure meat, the drier it gets, but at some point it will become so dry that it’s nearly impossible to slice and eat. So it’s not a Bordeaux, which you can keep for decades and it keeps getting better.

The meat needs to hang until it has lost 30% of its post-salting weight. (So make sure to weigh your meat after the salting and pressing!) For small cuts like young wild boar, this can happen in a few months. For a large 25 pound ham, it can take a year. These 14 ounce lonzas at left will probably be cured in a month or two. The 4 pound hams will probably be cured in 4-6 months. The longer you cure meat, the drier it gets, but at some point it will become so dry that it’s nearly impossible to slice and eat. So it’s not a Bordeaux, which you can keep for decades and it keeps getting better.

Aging (hanging) meat is an art. I’m no expert, and neither are you. Salumi artisans in Italy, who’ve been doing it since childhood using family techniques perfected across centuries, will stick a long thin bone into the prosciutto and remove it, and they can tell by the smell when the ham is ready to eat. And there are a HOST of things that can go wrong during the hanging phase…if you start getting any color of mold other than white growing on your meat, you need to wash it off with salted vinegar, and say an earnest prayer that the mold isn’t growing on the inside of the meat, as well. If you are curing in a cellar or basement, you have to be careful of pests, as well…mice and insects. (That’s less of a problem in a retrofitted fridge.) However, the best cured meats in the world come from damp, dingy, century-old, dirt-floored basements in Europe, and just like the French attitude toward wine, the Italians say that only Mother Nature can make salumi. If you start with a good pig, and have the right environment, excellent salumi will result.

Note the operative words there…”good pig.” You can’t go to the grocery store and buy a ham, and make superb prosciutto. Commercial pork is raised with a careful diet that makes it leaner than chicken. Such meat will NEVER produce even decent salumi. The Italians have heirloom breeds of pig that are renowned for having a high fat content, and they feed these pigs acorns…fruit…milk…and a variety of natural foods that produce meltingly-tender, fatty meat that is perfect for curing. So don’t bother going to the time and expense of home-curing unless you have a source for excellent meat. Luckily, there’s probably a pig farmer within a hundred miles of you who is raising heirloom pig breeds. Red wattle hogs are becoming the popular breed for American farmers to raise…they are much-loved in Italy. Craigslist is an excellent place to start, as is a visit to your local Agriculture Extension office. If you can find a source for hand-raised, heirloom-breed pork, then you’ve got the perfect starting point for making world-class salumi at home.

For an excellent primer on curing meats at home, check out Salumi: The Craft of Italian Dry Curing by Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn and Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting Smoking and Curing, by the same authors.

Subscribe to my blog in the window near the upper right corner of your screen, so you don’t miss my post on how to build a home curing room using an old fridge! And feel free to comment below…I’d love to hear any stories you have about home curing, or about great memories eating excellent cured meats!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.