After my seemingly endless blog about the underground restaurant FRANK that I run with my bestie Jennie Kelley from season 2 of MasterChef, I though I’d be done writing about FRANK for awhile. However, our Easter seatings in March were so incredibly epic and special, and so many of you have requested the story behind the menu, that I guess I’ll weave that tale in with the stories of our spring foraging in Texas.

Foraging, or harvesting food from the wild, used to be a way of life for many people in this country. It still is, for some. In fact, my family foraged out of necessity during a particularly impoverished part of my childhood. I grew up fairly close to the earth…raising sheep and pigs and chickens for meat, and my grandparents knew quite a lot about the wild foods that were abundant in South Texas. The gardens of my grandfathers fed not only our families, but many in the small hamlet of Lytle and the communities of South San Antonio where I spent my early childhood.

Foraging, or harvesting food from the wild, used to be a way of life for many people in this country. It still is, for some. In fact, my family foraged out of necessity during a particularly impoverished part of my childhood. I grew up fairly close to the earth…raising sheep and pigs and chickens for meat, and my grandparents knew quite a lot about the wild foods that were abundant in South Texas. The gardens of my grandfathers fed not only our families, but many in the small hamlet of Lytle and the communities of South San Antonio where I spent my early childhood.

So foraging has always been near and dear to my heart. Nowadays, foraging has been rediscovered by “foodies” and it has become terribly trendy to eat foraged ingredients at $100-a-plate restaurants (like FRANK…ahem…) From the earliest days of FRANK, Jennie and I knew we wanted to do many foraged menus, but it takes FAR more work to pull off a foraged dinner than to pick your ingredients from the garden or buy them from farmers. And, while foraging can be done in ANY season in the Dallas area, spring is ideal because there’s a LOT of wild food around, and the poison ivy is just beginning to wake up.

Poison ivy and poison oak abound in the parks and green spaces across North Texas. These plants produce an irritant called “urushiol” (pronounced “yoo-ROO-shee-awl”) that can cause a severe immune response in humans that produces wicked-crazy blisters on the skin. (Interesting factoid: cashews are rich in urushiol and have to be steamed to break down the toxins. So even when you buy “raw cashews” they are still cooked to remove the poison, they just haven’t been roasted yet.) The rash typically breaks out a day or two after exposure, and can last for a month. Contrary to folklore, poison ivy doesn’t spread on your body after exposure (unless you continue to be exposed to the urushiol oils from unwashed clothing or shoes, your dog, etc.) and you can’t pass it from person to person by contacting the rash (though if you still have the oil on your body, you CAN pass it to other people). Humans are the only known creatures that respond to poison ivy. And luckily, I’ve been literally WADING through poison ivy in shorts and a t-shirt my entire life, and I’ve never had an issue.

Poison ivy and poison oak abound in the parks and green spaces across North Texas. These plants produce an irritant called “urushiol” (pronounced “yoo-ROO-shee-awl”) that can cause a severe immune response in humans that produces wicked-crazy blisters on the skin. (Interesting factoid: cashews are rich in urushiol and have to be steamed to break down the toxins. So even when you buy “raw cashews” they are still cooked to remove the poison, they just haven’t been roasted yet.) The rash typically breaks out a day or two after exposure, and can last for a month. Contrary to folklore, poison ivy doesn’t spread on your body after exposure (unless you continue to be exposed to the urushiol oils from unwashed clothing or shoes, your dog, etc.) and you can’t pass it from person to person by contacting the rash (though if you still have the oil on your body, you CAN pass it to other people). Humans are the only known creatures that respond to poison ivy. And luckily, I’ve been literally WADING through poison ivy in shorts and a t-shirt my entire life, and I’ve never had an issue.

That is…until foraging for FRANK the past few weeks! I got the rash all over my body, even on my face! The best way to deal with poison ivy is to immediately dust any area that came in contact with the plant with baking soda or corn starch. This helps to dry out the oils. (There are also some commercial soaps that will bind to the oils more effectively.) Once you’ve done this, you can shower gently, but DON’T scrub, as you may drag the oils across your skin, increasing the exposure. The rash will develop anywhere from a day to 4 or 5 days after exposure, and at that point, you just gotta keep it as dry as possible. Baking soda is a fabulous remedy, as is prescription-strength steroid cream, and the old standby, calamine lotion.

I’ve spent so much time discussing poison ivy because it’s the most common enemy you will face while foraging in the summer and fall in Texas, but in spring it’s just beginning to bud out. Even the bare dormant trunk can spread urushiol in the dead of winter, but when the leaves are out, there’s greater surface area on the plant to contact you. If you react to poison ivy, or if you’re not sure, wear long pants and long sleeves while foraging, and immediately and carefully remove clothes and shoes when you get home and wash them.

Now…all that said, spring foraging can be VERY plentiful in north Texas (and all over the country, for that matter), so we were dead set on having a foraged menu. And Easter seemed like a perfect time, because while everyone else was hunting for eggs, we were hunting for delicious wild goodies for our guests!

I am fortunate to live on a big forested park here in Lewisville called Central Park. It’s nowhere near the size of the famous one in Manhattan, but it’s plenty big enough to be bursting with edible goodies in the spring, and the first things to come up are the wild garlic chives. Often referred to as wild onions and wild garlic, these alliums are exploding with sweet garlicky-onion flavor and they grow so abundantly in the park that I could pick several pounds in about 15 minutes. Every bit of this plant is edible, from the little white root bulb, to the flat leaves, to the round hollow stem that sends up a gorgeous little green bulb that later opens into a lovely cluster of white flowers. In this picture you see a nice bunch of whole wild garlic chives, as well as a few handfuls of the buds. You can use the bottom white part just like scallions or green onions, though they have a bit more bite to them, so you can also use them like regular onions. The flat leaves can be sliced and used just like chives or green scallion. But the buds are the real gem. Saute them in butter with a bit of sugar and salt, and they are crisp and delicious. Perfect with scrambled eggs, in tacos, or, like we served them, with sauteed wild mushrooms. The only poisonous look-alike for wild garlic chive is called “crow poison” and it smells musty and NOTHING like onion. Wild garlic chives are unmistakeably oniony smelling.

I am fortunate to live on a big forested park here in Lewisville called Central Park. It’s nowhere near the size of the famous one in Manhattan, but it’s plenty big enough to be bursting with edible goodies in the spring, and the first things to come up are the wild garlic chives. Often referred to as wild onions and wild garlic, these alliums are exploding with sweet garlicky-onion flavor and they grow so abundantly in the park that I could pick several pounds in about 15 minutes. Every bit of this plant is edible, from the little white root bulb, to the flat leaves, to the round hollow stem that sends up a gorgeous little green bulb that later opens into a lovely cluster of white flowers. In this picture you see a nice bunch of whole wild garlic chives, as well as a few handfuls of the buds. You can use the bottom white part just like scallions or green onions, though they have a bit more bite to them, so you can also use them like regular onions. The flat leaves can be sliced and used just like chives or green scallion. But the buds are the real gem. Saute them in butter with a bit of sugar and salt, and they are crisp and delicious. Perfect with scrambled eggs, in tacos, or, like we served them, with sauteed wild mushrooms. The only poisonous look-alike for wild garlic chive is called “crow poison” and it smells musty and NOTHING like onion. Wild garlic chives are unmistakeably oniony smelling.

The park also yielded several lovely bunches of wood sorrel, also called oxalis. Most people refer to this plant as clover, though true clovers (while edible) don’t have nearly the flavor of wood sorrel. They also don’t have the heart-shaped leaves like sorrel. Sorrel is one of the most common weeds out there, and if you come across some, it’s so easy to identify and has no poisonous look-alikes. Next time you run across some, have a taste. It’s like a burst of lemon and tart berry in your mouth. So delicious it will shock you!

The park also yielded several lovely bunches of wood sorrel, also called oxalis. Most people refer to this plant as clover, though true clovers (while edible) don’t have nearly the flavor of wood sorrel. They also don’t have the heart-shaped leaves like sorrel. Sorrel is one of the most common weeds out there, and if you come across some, it’s so easy to identify and has no poisonous look-alikes. Next time you run across some, have a taste. It’s like a burst of lemon and tart berry in your mouth. So delicious it will shock you!

This is also the time that wild mustard goes crazy in our open fields, and there was plenty of it in the park. Wild mustard is the exact same plant as the mustard greens you get in the store, it’s just that those have been selectively bred to produce larger leaves and take longer before they send up the blossom stalk. The flavor of wild mustard is explosive, and all parts of the plant above ground are edible, from the tender, tangy leaves to the peppery broccoli-like buds to the pungent yellow blossoms. And wild mustard is EVERYWHERE. Within a 5 minute walk of my house, I could harvest hundreds of pounds of it. (And I live in a normal neighborhood with a greenbelt park running through it.) Mustard, in the same family as broccoli, kale, cabbage, and turnips, is one of the healthiest greens on the planet, packed with cancer-fighting compounds, and overloaded with vitamins and minerals. And mustard is probably the single most common weed anywhere on the globe. It’s everywhere. Next time you’re driving past an open space and see little yellow flowers on top of a leafy stalk, you’re looking at wild mustard. It has no poisonous look-alikes. If you can find a plant that grows in at least partial shade, it will have larger leaves than those growing in full sun. The flavor is incredible, so eat up!

This is also the time that wild mustard goes crazy in our open fields, and there was plenty of it in the park. Wild mustard is the exact same plant as the mustard greens you get in the store, it’s just that those have been selectively bred to produce larger leaves and take longer before they send up the blossom stalk. The flavor of wild mustard is explosive, and all parts of the plant above ground are edible, from the tender, tangy leaves to the peppery broccoli-like buds to the pungent yellow blossoms. And wild mustard is EVERYWHERE. Within a 5 minute walk of my house, I could harvest hundreds of pounds of it. (And I live in a normal neighborhood with a greenbelt park running through it.) Mustard, in the same family as broccoli, kale, cabbage, and turnips, is one of the healthiest greens on the planet, packed with cancer-fighting compounds, and overloaded with vitamins and minerals. And mustard is probably the single most common weed anywhere on the globe. It’s everywhere. Next time you’re driving past an open space and see little yellow flowers on top of a leafy stalk, you’re looking at wild mustard. It has no poisonous look-alikes. If you can find a plant that grows in at least partial shade, it will have larger leaves than those growing in full sun. The flavor is incredible, so eat up!

I have some favorite spots in the park where I regularly find wild oyster mushrooms after a good rain, and while my normal spots didn’t yield anything, a still-standing dead tree did give us a pound of wild oysters! Foraging for wild mushrooms can be a dangerous endeavor if you’re not careful, but luckily, oyster mushrooms have NO poisonous look-alikes. If you find an earth-colored mushroom (it can be any color from white to cream to tan to brown) growing on dead wood that has no central stalk…the oyster blooms right out of the wood from a small stalk on its side…and the gills on the underside run downward along the stalk, you’ve found an oyster mushroom and you can safely eat it. Wild oysters smell a bit like the sea, and I find them to be incredibly delicious. Unfortunately, so do the bugs, so unless you’ve found just-sprouted oysters, they’re likely to be riddled with beetle holes. (That doesn’t always stop me from eating them, but I wouldn’t serve buggy oysters at a fancy place like FRANK!) Wild oysters grow all over the US. Look for them on dead wood in damp areas, or after an extended rain. They are among the most common mushrooms out there.

I have some favorite spots in the park where I regularly find wild oyster mushrooms after a good rain, and while my normal spots didn’t yield anything, a still-standing dead tree did give us a pound of wild oysters! Foraging for wild mushrooms can be a dangerous endeavor if you’re not careful, but luckily, oyster mushrooms have NO poisonous look-alikes. If you find an earth-colored mushroom (it can be any color from white to cream to tan to brown) growing on dead wood that has no central stalk…the oyster blooms right out of the wood from a small stalk on its side…and the gills on the underside run downward along the stalk, you’ve found an oyster mushroom and you can safely eat it. Wild oysters smell a bit like the sea, and I find them to be incredibly delicious. Unfortunately, so do the bugs, so unless you’ve found just-sprouted oysters, they’re likely to be riddled with beetle holes. (That doesn’t always stop me from eating them, but I wouldn’t serve buggy oysters at a fancy place like FRANK!) Wild oysters grow all over the US. Look for them on dead wood in damp areas, or after an extended rain. They are among the most common mushrooms out there.

We also discovered some stupendously-large wild mushrooms on a damp log, one of which weighed over a POUND! At first, they looked like chanterelles, but it’s a bit too early in the season for them, and chanterelles do not EVER grow on dead wood, only in the soil. The chanterelle has only one poisonous look-alike, which is the jack o lantern mushroom. Which DOES grow on dead wood. So while this mushroom isn’t quite as orange as a normal jackolantern, all its other characteristics indicate that it was. Jackolanterns aren’t deadly, they’ll just land you in the bathroom for a few days. I still picked it and plan to dry it out as a mushroom-hunting trophy. It smelled like cheese and apricots and really impressed our Easter Sunday diners at FRANK.

We also discovered some stupendously-large wild mushrooms on a damp log, one of which weighed over a POUND! At first, they looked like chanterelles, but it’s a bit too early in the season for them, and chanterelles do not EVER grow on dead wood, only in the soil. The chanterelle has only one poisonous look-alike, which is the jack o lantern mushroom. Which DOES grow on dead wood. So while this mushroom isn’t quite as orange as a normal jackolantern, all its other characteristics indicate that it was. Jackolanterns aren’t deadly, they’ll just land you in the bathroom for a few days. I still picked it and plan to dry it out as a mushroom-hunting trophy. It smelled like cheese and apricots and really impressed our Easter Sunday diners at FRANK.

The 40 acre park’s last gift to us was redbud blossoms. The redbud tree is a native to Texas, and while most of us are accustomed to seeing them landscaped into yards, they grow rampantly in the wild, as well. And virtually nobody knows that the blossoms are truly delicious. Sweet to begin with, with a slight floral aroma, then tart on the tongue, and finishing with a very green, grassy flavor like sugar snap peas. They are an incredible addition to salads, with an eye-popping color and a surprisingly crisp texture. So this gives you yet another reason to be jealous of your neighbor’s tree, burdened down with pink-purple blossoms each spring!

The 40 acre park’s last gift to us was redbud blossoms. The redbud tree is a native to Texas, and while most of us are accustomed to seeing them landscaped into yards, they grow rampantly in the wild, as well. And virtually nobody knows that the blossoms are truly delicious. Sweet to begin with, with a slight floral aroma, then tart on the tongue, and finishing with a very green, grassy flavor like sugar snap peas. They are an incredible addition to salads, with an eye-popping color and a surprisingly crisp texture. So this gives you yet another reason to be jealous of your neighbor’s tree, burdened down with pink-purple blossoms each spring!

Late March is morel mushroom season in Texas. And yes…we have morels here. Lots of them. I know a guy who pulls out 30-40 pounds of them from a park near Waco each year. They are found all across the Dallas metroplex in parks that have hardwood trees like elm and sycamore, north all the way into Oklahoma, and south to Austin. In fact, Dallas marks the westerly boundary of common morel territory before you reach the southwestern deserts. (Though they are found in moist mountainous regions, and are prolific in the Pacific Northwest.) So Jennie and I were determined to find our diners some wild Dallas morels. Unfortunately, it has been an uncommonly dry, hot spring, and morels like damp weather that slowly warms into the 80s but with cool nights. Some years produce bumper crops of Texas morels. Some years, experts are lucky to find a handful. And the reports this year indicated that we’d be out of luck…only a few morel finds have been reported in Texas, most of them near Tyler, but a few north of Denton. So Jennie and I headed to the hardwood river bottoms along the Trinity River north of Lake Lewisville to see what we could find.

No morels in sight after several hours of foraging, but Jennie made her first wild mushroom find in a hollow beneath a fallen tree. Mica caps! Which are very edible. You can see the little boogers hiding toward the bottom center of the photo. Mica caps belong to a family of wild mushrooms called “inky caps,” many of which are edible, but some of which have a bizarre habit of reacting badly in the digestive system with alcohol. If you consume alcohol even within several days of eating some inky caps, you’ll vomit violently. (Compounds isolated from these mushrooms have been used to produce medicines to treat alcoholism, because of this unique trait.) Fortunately, mica caps are delicious and completely edible, but their dark gills are so small and delicate that they begin to decompose into a black slime soon after picking and need to be cooked within 4 hours. By the time we began cooking for FRANK, most of them were goners, but we were able to include a few. And to be sure they were safe for our diners, we ate them the day before and had more than a bit of wine and beer…just to be on the safe side! I’m not going to to into descriptions of the inky caps because mushroom identification for this species is well beyond the scope of this blog entry. If you’re interested in mushroom foraging, you need to have at least 2 solid field guides in your possession and make a positive identification before consuming ANY wild mushroom. Some favorite guides are Edible Wild Mushrooms of North America by David Fischer, The Complete Mushroom Hunter by Gary Lincoff, and for fellow Texans, Texas Mushrooms by Susan and Van Metzler (currently out of print and becoming rare, so snatch it up!)

No morels in sight after several hours of foraging, but Jennie made her first wild mushroom find in a hollow beneath a fallen tree. Mica caps! Which are very edible. You can see the little boogers hiding toward the bottom center of the photo. Mica caps belong to a family of wild mushrooms called “inky caps,” many of which are edible, but some of which have a bizarre habit of reacting badly in the digestive system with alcohol. If you consume alcohol even within several days of eating some inky caps, you’ll vomit violently. (Compounds isolated from these mushrooms have been used to produce medicines to treat alcoholism, because of this unique trait.) Fortunately, mica caps are delicious and completely edible, but their dark gills are so small and delicate that they begin to decompose into a black slime soon after picking and need to be cooked within 4 hours. By the time we began cooking for FRANK, most of them were goners, but we were able to include a few. And to be sure they were safe for our diners, we ate them the day before and had more than a bit of wine and beer…just to be on the safe side! I’m not going to to into descriptions of the inky caps because mushroom identification for this species is well beyond the scope of this blog entry. If you’re interested in mushroom foraging, you need to have at least 2 solid field guides in your possession and make a positive identification before consuming ANY wild mushroom. Some favorite guides are Edible Wild Mushrooms of North America by David Fischer, The Complete Mushroom Hunter by Gary Lincoff, and for fellow Texans, Texas Mushrooms by Susan and Van Metzler (currently out of print and becoming rare, so snatch it up!)

Along Clear Creek just west of its confluence with the Trinity River, we happened across another very common weed that happens to be eminently delicious…chickweed. Chickweed grows everywhere, from landscaped planter beds to the deep woods. It grows prolifically in the Texas winter and early spring, and is one of the most common green things to survive year round. Chickweed is crunchy and sweet, a great base for salads. It’s easy to identify with its sturdy stems that spread along the ground, little oblong pointy leaves, and dainty white blossoms. It grows all over the US, except in the driest desert regions, and has no poisonous look-alikes. We stuffed several gallon-size ziplocs in less than 5 minutes, and had a great base for our salad. Chickweed is sturdy and holds up well in the fridge, too, whereas other wild greens like sorrel and mustard can wilt unless you pick them by the root and keep the roots moist until just before prepping and serving.

Along Clear Creek just west of its confluence with the Trinity River, we happened across another very common weed that happens to be eminently delicious…chickweed. Chickweed grows everywhere, from landscaped planter beds to the deep woods. It grows prolifically in the Texas winter and early spring, and is one of the most common green things to survive year round. Chickweed is crunchy and sweet, a great base for salads. It’s easy to identify with its sturdy stems that spread along the ground, little oblong pointy leaves, and dainty white blossoms. It grows all over the US, except in the driest desert regions, and has no poisonous look-alikes. We stuffed several gallon-size ziplocs in less than 5 minutes, and had a great base for our salad. Chickweed is sturdy and holds up well in the fridge, too, whereas other wild greens like sorrel and mustard can wilt unless you pick them by the root and keep the roots moist until just before prepping and serving.

All foraged greens can be improved by shocking them in ice water for 30 minutes, then storing in the coldest part of your fridge until serving time. Never dress wild greens until the very last instant, as the acid in dressings can begin breaking them down much faster than store-bought lettuces.

On our hike back to the car, we were viciously attacked by one of the most dangerous of predators you can face whilst foraging:

I jest. This little critter couldn’t hurt a flea. This is a 9-banded armadillo, and while it looks reptilian, it’s a mammal like you and me. Armadillos are common in Texas, and they have such horrible eyesight that they usually have no clue that you’re around. This little guy was snorting and rooting around in the dirt for bugs and tender shoots and walked right up to my foot before he smelled us and high-tailed it into the woods. It’s always a delight to run into wildlife when foraging. It reminds you of the balance of the natural world, and it really brings things into perspective when you realize that this little guy forages almost every waking instant of his life.

I jest. This little critter couldn’t hurt a flea. This is a 9-banded armadillo, and while it looks reptilian, it’s a mammal like you and me. Armadillos are common in Texas, and they have such horrible eyesight that they usually have no clue that you’re around. This little guy was snorting and rooting around in the dirt for bugs and tender shoots and walked right up to my foot before he smelled us and high-tailed it into the woods. It’s always a delight to run into wildlife when foraging. It reminds you of the balance of the natural world, and it really brings things into perspective when you realize that this little guy forages almost every waking instant of his life.

The clock is ticking and we have a FRANK to put on in a few short days, but there’s more left to forage. This time, even closer to home. Neighbor Sharon has a side yard absolutely bursting with dandelions, so I spent one morning picking the beautiful golden blossoms. All parts of the dandelion plant are edible. The roots are roasted and ground to make chicory, which tastes like mild, nutty coffee. The young leaves are delicious with a pleasant mild bitterness, like arugula, before the plant blossoms. The yellow petals of the flower are fragrant and floral and entirely edible, though the green sepal that holds the petals together can be bitter. The blossoms can be added to salads and cocktails, or boiled with sugar and fermented into a very floral wine. When I shared this photo on Facebook, a delightful fan named Katja Turk mentioned that her grandmothers in Slovenia used to make a syrup from the blossoms that would substitute for honey, which was too expensive for them to afford in the communist era. She generously shared the recipe with me, and it sounded so intriguing that I had to make it. It turned out to be Jennie’s favorite component of the entire menu. Check out the very simple recipe here! And thanks, Katja!!!

The clock is ticking and we have a FRANK to put on in a few short days, but there’s more left to forage. This time, even closer to home. Neighbor Sharon has a side yard absolutely bursting with dandelions, so I spent one morning picking the beautiful golden blossoms. All parts of the dandelion plant are edible. The roots are roasted and ground to make chicory, which tastes like mild, nutty coffee. The young leaves are delicious with a pleasant mild bitterness, like arugula, before the plant blossoms. The yellow petals of the flower are fragrant and floral and entirely edible, though the green sepal that holds the petals together can be bitter. The blossoms can be added to salads and cocktails, or boiled with sugar and fermented into a very floral wine. When I shared this photo on Facebook, a delightful fan named Katja Turk mentioned that her grandmothers in Slovenia used to make a syrup from the blossoms that would substitute for honey, which was too expensive for them to afford in the communist era. She generously shared the recipe with me, and it sounded so intriguing that I had to make it. It turned out to be Jennie’s favorite component of the entire menu. Check out the very simple recipe here! And thanks, Katja!!!

Some of the foraged items on the menu aren’t foraged by us. Tom Spicer, a local purveyor legendary in the Dallas restaurant community, has a fantastic little shop near the popular Jimmy’s Deli, called Spiceman’s FM 1410. He’s open to the public, and if you’re ever looking for a fascinating field trip, head to Tom’s place. He has a massive garden out back, where his employees and friends are usually gathered around a bottle of wine or a pot of something yummy they’ve just cooked up. And in the front are boxes filled with wild foraged ingredients flown in from the Pacific Northwest. What he’s got varies dramatically by season, but you’re likely to find wild mushrooms year round, and sometimes fiddlehead ferns, truffles, and the like. Tom has provided us with black trumpet mushrooms (a cool-season relative of the chanterelle, which also grows in Texas under the right conditions), as well as Oregon white truffles, and some beautiful wild mustard raab (related to the wild mustard we foraged, but with a larger, broccoli-like flowering head).

Some of the foraged items on the menu aren’t foraged by us. Tom Spicer, a local purveyor legendary in the Dallas restaurant community, has a fantastic little shop near the popular Jimmy’s Deli, called Spiceman’s FM 1410. He’s open to the public, and if you’re ever looking for a fascinating field trip, head to Tom’s place. He has a massive garden out back, where his employees and friends are usually gathered around a bottle of wine or a pot of something yummy they’ve just cooked up. And in the front are boxes filled with wild foraged ingredients flown in from the Pacific Northwest. What he’s got varies dramatically by season, but you’re likely to find wild mushrooms year round, and sometimes fiddlehead ferns, truffles, and the like. Tom has provided us with black trumpet mushrooms (a cool-season relative of the chanterelle, which also grows in Texas under the right conditions), as well as Oregon white truffles, and some beautiful wild mustard raab (related to the wild mustard we foraged, but with a larger, broccoli-like flowering head).

So now we’re in the FRANK kitchen, turning all our foraged goodies into 5 courses for our guests. The first course, which I don’t have a photo of (sorry), is a deviled egg topped with crispy sauteed white truffles. And these are no ordinary eggs…these are pastured eggs from farmer William Hurst at Grandma’s Farm in McKinney. (Yes, he sells to the public!) William’s chickens live the way chickens should…completely free-ranging wherever they please during the day. (They instinctively return to the safety of the coop at night, when predators are out.) The label “free range” that you see on egg cartons in the grocery store is misleading. It just means that the chickens don’t live in a 2′ square cage. They might live in an 8′ cage, where they can “free range” across all 64 square feet of that cage (along with the other 10 hens living in that same cage). Or it can mean that once a day the chickens are let out of their cage into a pen for half an hour. It doesn’t mean the chickens are fulfilling their natural lifestyle, foraging for bugs and weeds all over the pasture. To get those kind of eggs, you have to either buy from a farmer, or fork over $10 a dozen to get labeled “pastured eggs” at a gourmet market. The difference in quality is like night and day. The only drawback to using such fresh, high quality eggs is that they can be nearly impossible to peel cleanly for good presentation. It takes HOURS to peel the eggs so that they are pretty enough to present to the FRANK audience. The yolks are deviled with lots of mustard and vinegar, and then we gently saute the chopped white truffles in butter to bring out their aroma and once they are nice and crisp, we sprinkle them on top of the deviled egg. (We served this course with a glass of champagne accompanied by a whole kumquat that was candied in the dandelion syrup mentioned above!) This introduces our menu as uniquely American…one of the first true American menus we’ve served at FRANK.

Course two is a wild salad of mustard greens, lemony wood sorrel, and crisp-sweet chickweed, with redbud blossoms, tossed in a wild garlic chive vinaigrette. Accompanying this is tender rabbit loin that we’ve brined briefly, then wrapped in house-cured wild boar prosciutto. (You may recall my blog post about my neighbor Ron bringing me a wild boar last fall, and I built a curing chamber out of an old fridge in my garage to cure it into prosciutto using a traditional Italian recipe.) We sauteed the wrapped loins briefly to crisp up the prosciutto, leaving the tiny morsels of rabbit loin at medium. If you’ve never tasted rabbit loin, you just don’t know what you’re missing. It is meltingly tender, delicately flavored, and a perfect pairing with wild boar. Our rabbits were raised by an artisan breeder in Quebec up in Canada, where they raise heirloom breeds from France. (Rabbit remains a VERY popular meat in France and Spain.) But we had to buy the rabbits whole, so we used the bones and leg meat in another course, to be certain not to waste anything. At this point we also pass around the homemade garlic chive sourdough, which our guests can spread homemade white truffle butter on.

Course two is a wild salad of mustard greens, lemony wood sorrel, and crisp-sweet chickweed, with redbud blossoms, tossed in a wild garlic chive vinaigrette. Accompanying this is tender rabbit loin that we’ve brined briefly, then wrapped in house-cured wild boar prosciutto. (You may recall my blog post about my neighbor Ron bringing me a wild boar last fall, and I built a curing chamber out of an old fridge in my garage to cure it into prosciutto using a traditional Italian recipe.) We sauteed the wrapped loins briefly to crisp up the prosciutto, leaving the tiny morsels of rabbit loin at medium. If you’ve never tasted rabbit loin, you just don’t know what you’re missing. It is meltingly tender, delicately flavored, and a perfect pairing with wild boar. Our rabbits were raised by an artisan breeder in Quebec up in Canada, where they raise heirloom breeds from France. (Rabbit remains a VERY popular meat in France and Spain.) But we had to buy the rabbits whole, so we used the bones and leg meat in another course, to be certain not to waste anything. At this point we also pass around the homemade garlic chive sourdough, which our guests can spread homemade white truffle butter on.

Next comes the pasta course. Hand-rolled tagliatelle (a micro-thin pasta just a bit wider than fettucini) with a medley of wild mushrooms and wild onion buds. While the pasta may be

Next comes the pasta course. Hand-rolled tagliatelle (a micro-thin pasta just a bit wider than fettucini) with a medley of wild mushrooms and wild onion buds. While the pasta may be  Italian, this is decidedly an American dish. The mushrooms (wild oysters, wild black trumpets, wild mica caps, plus cultivated maitake/hen of the woods, beech mushrooms, and enokis) are sauteed in very small batches in butter, allowing them to brown up just like meat. They are then tossed with gorgeous wild onion buds, the unopened flower at the top of the plant, which we sauteed with olive oil and a bit of sugar to open up the flavor. Then we let them all sit for a few hours, so the flavors can mingle. The texture is amazing…good crunch from the onion buds, a big variety of textures from the mushrooms (firm oysters, delicate black trumpets, crispy enokis, tender maitakes), and the fairy-like delicacy of the pasta, which was tossed in a tangy, light cream sauce infused with white truffle. This was a favorite course for many of our diners, and some even said that the pasta surpassed the housemade pastas at Dallas’s finest Italian restaurant in the Bishop Arts District! (Name not included so we don’t sound like we’re bragging.)

Italian, this is decidedly an American dish. The mushrooms (wild oysters, wild black trumpets, wild mica caps, plus cultivated maitake/hen of the woods, beech mushrooms, and enokis) are sauteed in very small batches in butter, allowing them to brown up just like meat. They are then tossed with gorgeous wild onion buds, the unopened flower at the top of the plant, which we sauteed with olive oil and a bit of sugar to open up the flavor. Then we let them all sit for a few hours, so the flavors can mingle. The texture is amazing…good crunch from the onion buds, a big variety of textures from the mushrooms (firm oysters, delicate black trumpets, crispy enokis, tender maitakes), and the fairy-like delicacy of the pasta, which was tossed in a tangy, light cream sauce infused with white truffle. This was a favorite course for many of our diners, and some even said that the pasta surpassed the housemade pastas at Dallas’s finest Italian restaurant in the Bishop Arts District! (Name not included so we don’t sound like we’re bragging.)

And now the main attraction…probably my favorite course we’ve EVER served at any FRANK. This is a pink peppercorn encrusted, bone-in venison chop, cooked medium rare. We got some extraordinary venison racks from one of our amazing purveyors, Clark at Arrowhead Specialty Meats in Lewisville. (Clark is also happy to sell to the public, and he’s got some amazing stuff…prime Texas Wagyu beef, kangaroo, heirloom duck, local quail, etc.) The pink peppercorns I foraged on a recent trip to Hawaii from a tree growing in my friends’ neighborhood, and they’ve appeared on the FRANK menu before. The venison was brined to help keep it moist…venison is a VERY lean meat and it overcooks in a second (remember how I got eliminated from MasterChef?!?) so brining is crucial to ensure juiciness. And then it’s roasted just to 125F and allowed to coast to medium rare for 20 minutes on the countertop before slicing.

And now the main attraction…probably my favorite course we’ve EVER served at any FRANK. This is a pink peppercorn encrusted, bone-in venison chop, cooked medium rare. We got some extraordinary venison racks from one of our amazing purveyors, Clark at Arrowhead Specialty Meats in Lewisville. (Clark is also happy to sell to the public, and he’s got some amazing stuff…prime Texas Wagyu beef, kangaroo, heirloom duck, local quail, etc.) The pink peppercorns I foraged on a recent trip to Hawaii from a tree growing in my friends’ neighborhood, and they’ve appeared on the FRANK menu before. The venison was brined to help keep it moist…venison is a VERY lean meat and it overcooks in a second (remember how I got eliminated from MasterChef?!?) so brining is crucial to ensure juiciness. And then it’s roasted just to 125F and allowed to coast to medium rare for 20 minutes on the countertop before slicing.

The venison chop is served on a bed of braised rabbit leg meat. I mentioned earlier that, in order to be able to serve rabbit loin, we had to buy whole rabbits from the artisan breeder. Not wanting to waste ANY of these very special (and VERY expensive!) animals, we took the rib bones and organ meats and made a rich stock with them. That stock was used both in the cream sauce for the pasta course, as well as to braise the leg meat. So first we seasoned and seared the legs:

Then they went into the pot with the rabbit stock, along with wild onions, garlic, and fennel. (Rabbit and fennel is one of my favorite combinations.) We braised it low and slow…250F for a few hours, until the meat was fall-off-the-bone tender. One of the challenges of cooking rabbit meat is that the legs muscles are used so frequently to hop that the fibers can be very tough. And even a long, slow braise won’t break down the long chains of muscle fibers, though it WILL separate them. So no matter how you cook it, rabbit legs will always have chewy meat. But the slower and moister your cooking method, the more the fibers will separate, allowing the braising liquid to bathe and surround them, which means it will be moist when you eat it…and if you get it “just right” then the meat will have a very pleasant body to it, with a bit more “chew” than chicken.

On the plate with our venison and rabbit (2 game meats that our country grew up on) is some seared broccolini and some roasted fingerling potatoes, along with a compound butter made from wild garlic chives. And the sauce was VERY special, made from a reduction of a “foraged” Tawny Port-style wine I made 5 years ago with wild blackberries I picked near Mt. Rainier in Washington, and wild grapes I picked in the park behind my house. It was a perfect compliment to the venison. The final plate:

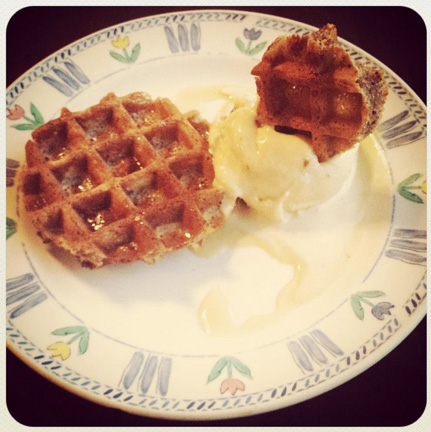

Of course, that’s not all, folks. Dessert follows, and is always a favorite at FRANK. This dessert was a bit more simple than previous desserts, because we really wanted to feature foraged flavors. 3 components only to dessert, and each component’s primary flavor was foraged. First we’ve got a waffle made with acorn and buckwheat. The acorns we foraged from a live oak tree and Michael Chen shelled each one of them individually. Some species of oak produce better acorns than others…live oak acorns tend to be lower in tannins and higher in sugars than most, so they work much better. But, they are smaller, which means LOTS of shelling! Once you’ve got the acorns shelled, you put them in a blender with water and puree them into a slurry. Then you strain the acorn mush in a dish towel and squeeze out the liquid. Then you return the mush to a bowl with extra water for a series of 15-minute soaks to help extract tannins, which add a bitter taste and “fuzzy” feeling on your tongue (like when you drink a young Bordeaux or Cabernet). You keep doing these flushes until the water coming off the acorn mush is clear and doesn’t taste bitter. Ours took only 3 flushes. Then you squeeze out all the water you can, spread the mush in a baking sheet, and bake at 170F for an hour or so, stirring every few minutes, until the mixture is a dry meal, almost crispy. Then whizz that in your blender or food processor and you’ve got acorn flour! It adds a nutty, sweet crunch to baked goods and pastas…but it’s a LOT of work. We also whizzed up some buckwheat groats in the blender to make buckwheat flour, and I modified my go-to waffle recipe with these wild ingredients. We were concerned that the waffle would end up dense and thick, but it was light, airy, and crisp. And drizzled with the dandelion syrup, it was downright divine. I’d venture a guess that more than half the guests at each FRANK told us it was the best waffle they had ever eaten.

Of course, that’s not all, folks. Dessert follows, and is always a favorite at FRANK. This dessert was a bit more simple than previous desserts, because we really wanted to feature foraged flavors. 3 components only to dessert, and each component’s primary flavor was foraged. First we’ve got a waffle made with acorn and buckwheat. The acorns we foraged from a live oak tree and Michael Chen shelled each one of them individually. Some species of oak produce better acorns than others…live oak acorns tend to be lower in tannins and higher in sugars than most, so they work much better. But, they are smaller, which means LOTS of shelling! Once you’ve got the acorns shelled, you put them in a blender with water and puree them into a slurry. Then you strain the acorn mush in a dish towel and squeeze out the liquid. Then you return the mush to a bowl with extra water for a series of 15-minute soaks to help extract tannins, which add a bitter taste and “fuzzy” feeling on your tongue (like when you drink a young Bordeaux or Cabernet). You keep doing these flushes until the water coming off the acorn mush is clear and doesn’t taste bitter. Ours took only 3 flushes. Then you squeeze out all the water you can, spread the mush in a baking sheet, and bake at 170F for an hour or so, stirring every few minutes, until the mixture is a dry meal, almost crispy. Then whizz that in your blender or food processor and you’ve got acorn flour! It adds a nutty, sweet crunch to baked goods and pastas…but it’s a LOT of work. We also whizzed up some buckwheat groats in the blender to make buckwheat flour, and I modified my go-to waffle recipe with these wild ingredients. We were concerned that the waffle would end up dense and thick, but it was light, airy, and crisp. And drizzled with the dandelion syrup, it was downright divine. I’d venture a guess that more than half the guests at each FRANK told us it was the best waffle they had ever eaten.

We served the waffle with my infamous Butter Pecan ice cream…a recipe I’ve been perfecting for almost a decade, like my famous pumpkin carrot cake. Friends demand it each year for 4th of July fireworks. The pecans were foraged from a local yard and shelled by hand by my neighbor Sharon.

We served the waffle with my infamous Butter Pecan ice cream…a recipe I’ve been perfecting for almost a decade, like my famous pumpkin carrot cake. Friends demand it each year for 4th of July fireworks. The pecans were foraged from a local yard and shelled by hand by my neighbor Sharon.

And thus ended what is easily the most epic and involved menu FRANK has served to date. While it’s cheaper, in terms of cash outlay, to serve a foraged meal, the hours involved in foraging ingredients and transforming them into masterpieces EXPONENTIALLY exceeds that of a regular dinner. However, our diners all agreed it was very much worth it.

I hope this blog entry encourages you to do a bit of foraging around your home and seeing what you come up with. Some very edible plants are easily recognized. If you’re interested in foraging, some books I highly recommend (in addition to the ones mentioned earlier) include The Forager’s Harvest and Nature’s Garden, both by Samuel Thayer, and ANY of the classics written by Euell Gibbons, the father of modern foraging.

Please feel free to post comments below, especially if you have your own stories about foraging!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.